-

Lecture 3

- The Young Learner 30 minLecture1.1

- The Foreign Language 10 secLecture1.2

- The Communicative Context 30 minLecture1.3

-

-

Teacher Education Tasks 6

- Task 1 20 minLecture2.1

- Task 2 10 minLecture2.2

- Appendix 1 10 minLecture2.3

- Appendix 2 10 minLecture2.4

- Appendix 3 10 minLecture2.5

- Appendix 4 20 minLecture2.6

-

-

Assessment & Reflection 2

- Module 1 – Theory 5 questionsQuiz3.1

- Module 1 – Practice 1 questionQuiz3.2

-

-

Activities 1

- Module 1 Activities 30 minLecture4.1

-

-

References 1

- References 30 minLecture5.1

-

The Young Learner

It is extremely important to constantly consider the different developmental stages of children at specific ages to adjust your attitudes towards your pupils as well as your teaching praxis. So, we will start with the theories which have largely investigated the close interrelation between children’s cognitive development and language acquisition.

Let’s start with Piaget (1923) who described the thought processes of the child to understand the course of early language acquisition (Fig.1). According to his view, before using words, children use actions to show recognition of objects and to represent intended activities. In early childhood, representation is tied to concrete events which the child has experienced and one product of the early development is the growth of the symbolic function. The whole process is ‘self-motivating’, that is motivation is intrinsic and not reinforced by external factors. The child is always able to construct the novel language in terms of the familiar. Thus, if an unfamiliar utterance occurs, he will not fail to respond to it, but he will try to make sense of it in terms of patterns which are familiar to him. This will happen at all levels of language (the lexical, phonological, morphological and syntactic level).

Of course, several conditions may co-occur during L1/L2 processes. For example, whenever language is directed to the child, it refers to some action or event that is occurring in the environment. Even though a child has already developed complex visual and motor abilities, he may still be unable to perform complex cognitive tasks.

With his theory, Piaget not only emphasized the biological foundation of cognitive development parallel to language development, but he also highlighted the role of environment with which the child interacts accomodating his mental schemata (Allen & Pit Corder 1980: 312f). By reversing the direction of the cognitive process from thought to the social environment, Vygotsky’s ‘social constructivism’ (1978) assumed the social environment as the main triggering force for the learning process. Children deveop higher-order cognitive functions, including linguistic skills, through social interactions with adults or more acknowledgeable peers, which take place within a child’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), that is, slightly ahead of the learner’s independent ability (Vygotsky 1978: 86).

Bloom’s taxonomy (Fig.2) also shows the development of cognitive stages. Each stage is characterized by specific cognitive or thinking skills which represent processes our brain use when we think and learn. Learners progress from simple information processing or concrete thinking skills, such as identifying and organizing information (LOTS or low order thinking skills) to more complex, abstract thinking, such as reasoning, hypothesising and evaluating (HOTS or high order thinking skills).

Such skills, if adequately oriented by teachers, can result in effective learning skills enabling learners to effectively respond and perform specific language tasks.

At an individual level, on the other hand, other forces seem to enhance learning, i.e. the processing and organisation of information according to learner-specific characteristics. The concept of learning styles (Fig.4) is based on a model that groups students’ learning preferences into learning processes based on experiential learning through senses.

Therefore, identifying learners’ learning/cognitive styles is necessary to predict what kind of instructional strategies or methods would be most effective for a given individual to perform a given learning task.

In order to feel totally involved from a cognitive as well as emotional point of view, the learner needs to be involved in a learning experience based on ‘knowledge gaps’ in which new information is non-discordant with his/her previous knowledge in L1. Thus, to activate the mind and enable it to modify its cognitive architecture, learning must be ‘meaningful’. The main features of ‘meaningful learning’ are based on the following standpoints:

a. learning is total, that is it involves the cognitive, affective, emotional and social sphere;

b. learning is a constructive process, where new information come to be integrated in the learner’s previous knowledge;

c. the quality of learning in terms of memory persistency is largely influenced by motivation which depends on internal factors such as interest, pleasure and need for learning.

This model focuses on the development of motivation centered on learners’ curiosity about cultural, social, historical diversity. As a matter of fact, some important principles can be identified:

d. No learning can happen without the right motivation supported by the dynamic interest of the individual involved in the process

e. Feature of dynamism makes motivation extremely variable because it is determined by the individual nature of the learners

f. Main motivation to learn a FL relies on its nature as a means of communication of meaningful contents (as in Content and Language Integrated Learning/CLIL) and contact with other cultures.

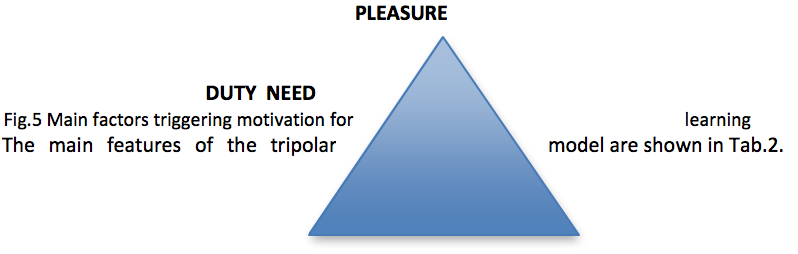

Given the cultural and social implications of motivation, some theorists (Freddi 1993; Balboni 1994, 2002) have proposed a tripolar model based on three potential factors triggering motivation such as duty, need and pleasure (Fig.5).

| MOTIVATION | DESCRIPTIONS | DEGREE OF LEARNING |

| PLEASURE | 1. reduced external conditioning 2. fulfillment of cognitive needs 3. personal involvement in participating in challenging class activities | 4. stable 5. stored in long-term memory 6. systemitized knowledge turned into personal competence |

| NEED | 1. connected to personal expectations and objectives (self-promotion, academic success) 2. based on BICS and CALP | Sometimes stable |

| DUTY | a. hetero-directed,i.e. prompted by external factors such as curriculum-based programmes, teacher-centred methodology b. self-directed | 1. highly unstable 2. stored in short-term memory 3. temporary |

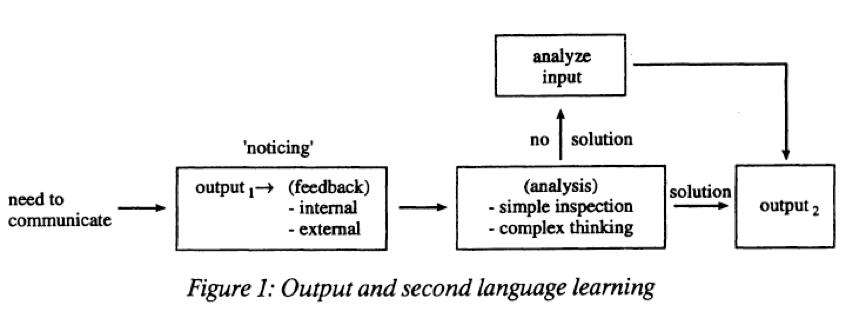

In terms of L2 acquisition theory, Krashen compared L2 acquisition to the process children use in acquiring L1. The central hypothesis of the Natural Approach is that similarly to L1 acquisition, SLA occurs by understanding aural messages through exposure to comprehensible input (Krashen & Terrell 1995: Preface). According to Krashen, exposure to meaningful input in the target language with a focus on the message rather than form is needed to acquire a language more than comprehensible output i.e. learner’s production since ‘there’s no direct evidence that comprehensible output leads to language acquisition’ and ‘high levels of linguistic competence are possible without output’ (1998: 178). A central role in the process of SLA is played, instead, by output within Swain and Lapkin’s model (1995). Output may set ‘noticing’ in train, triggering mental processes that lead to modified output, as an attention-getting / metalinguistic device. When facing a problem during the production of utterances, students may turn to input with more focused attention searching for relevant input or work out a solution resulting in new, reprocessed output (p.386). The stage/s between the first and the second output are considered part of the process of second language learning (Fig.1).